BY BRUCE KATZ, CENTENNIAL SCHOLAR AT THE BROOKINGS INSTITUTION, AUTHOR OF ‘THE METROPOLITAN REVOLUTION’, BOARD MEMBER OF BLOXHUB AND LEADING INTERNATIONAL EXPERT ON GLOBAL URBANIZATION.

Featured in: Economy, Real Estate

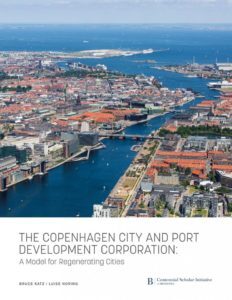

Thirty years ago, the city of Copenhagen was experiencing 17.5 percent unemployment, an outmigration of population, the loss of manufacturing, the decline of taxing capacity, and an annual budget deficit of $750 million. Today, the city has been transformed into one of the wealthiest (and happiest) in the world.

For the past eighteen months, Luise Noring of the Copenhagen Business School and I have examined one of the main reasons for this remarkable turnaround. Spoiler alert: it’s not cycling. Our focus – released today as a first-of-its-kind case study – has been on the Copenhagen City & Port Development Corporation (or By & Havn in Danish). The mayor of Copenhagen at the time, Jens Kramer Mikkelsen, put it as follows:

“We knew the city was in a desperate situation and we needed to [make large-scale infrastructure investments] to address this situation. However, to pay for the grand infrastructure project we needed serious money. We could not raise taxes. Also, we needed agility and flexibility to operate.”

The solution: transfer vast amounts of public land to a new publicly owned, privately managed corporation. Rezone the land – primarily in the old harbor and an undeveloped area between the airport and the downtown – for residential and commercial use. Then use the revenues projected by smart zoning and asset management — not taxes — to finance cross-city transit infrastructure, thereby spurring the regeneration of core areas of the city. The results of this institutional model have been nothing short of transformative. A vibrant, multi-purpose waterfront. A world class transit system. Thousands of housing units built for market and social purposes in accordance with energy-efficient standards. A portion of the harbor has even been partly built on surplus soil pulled up from the underground during the metro construction, raising the level of the new land by a meter as protection against climate change and rising sea levels. The Copenhagen model works because the public sector participates for the long term, reaping enormous benefits as value naturally appreciates from smart public investments. It combines the efficiency of market discipline and mechanisms with the benefits of public direction, legitimacy and low-cost finance. It is clear that adapting the model to U.S. cities as diverse as Hartford, Pittsburgh and Houston — and other cities around the world — would be enormously beneficial. But we have a long way to go.

In the U.S., we generally know what cities owe (due to massive pension liabilities) but not what they own. There is absolutely no excuse for this lack of transparency and market knowledge in the age of technological innovations like geospatial mapping and big data analytics. U.S. cities are often developing for the short- rather than long-term. The disposition of public assets in U.S. cities is often undertaken to fill immediate budget deficits rather than finance long term regeneration and infrastructure. The immediate budget needs of local government are exacerbated by the similar short-term orientation of financial institutions like commercial banks and pension funds. Public ownership in U.S. cities is actually quite large, but highly fragmented and balkanized. A blizzard of public institutions – airport authorities, port authorities, water and sewer authorities, convention center authorities, stadium authorities, redevelopment authorities, public housing authorities, land banks, school boards – co-own large amounts of the city but rarely align their management of assets for the broader good. To add insult to injury, many U.S. public authorities, initially established to ensure political insulation, are ironically riddled with political interference, the Port Authority of New York & New Jersey being only the most well-known example. Changing the culture and behavior of public authorities is as important as corporate or statutory issues of institutional merger and powers. Here is the bottom line: In the face of a radically changed economy, our cities need to upgrade outdated transportation and energy infrastructure and revitalize underutilized industrial and waterfront areas. Support from the federal and state governments at the right scale and in the appropriate form is highly unlikely. And exclusive reliance on the private sector is a fool’s errand, because it will prevent the public sector from enjoying the fruits of public assets. With the release of this report and the publication of Dag Detter and Stefan Folster’s The Public Wealth of Cities this summer, we hope to spark a conversation in the United States and beyond about a better way to grow, govern and finance our cities. There is something replicable in Denmark and we need to pay close attention.